My dad took me for a hot chocolate after school, in a café inside a church. The owner was short-staffed for the evening and asked if I had ever waited tables. I got my first proper job, to start that same day. My first salary in a professional kitchen.

Or, my parents were friends with the owner of a local café. I didn’t need a job at fourteen. Did I still receive pocket money? Or did they just pay for everything I needed?

Or, I grew up in a professional kitchen. My mother was a cooking teacher, and she gave classes in our home. Our kitchen had dozens of tart tins, a drawerful of electric mixers, more than one oven. My brother and I washed up some Saturdays for pocket money.

My dad had the time and the money to drive me into town on Saturdays to earn £4/hour for four hours. Because we lived in the countryside with a very irregular bus route. Because we lived in a big house in the countryside and didn’t need to rely on public transport. Because we had a garden and two cars.

–

This was supposed to be about time and love and I started in the wrong place –

–

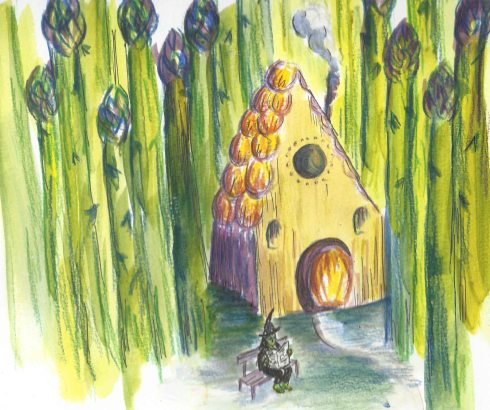

I cleared tables on the mezzanine in the nave. I carefully balanced the heavy trays on the way down the curving staircase and put the dishes through the dishwasher. I listened to the Georgian baker humming as he shaped flat, olive oil rolls for the sandwiches. I refilled the cutlery and paper napkins. I wiped the tables facing the pews. I checked the toilets and washed my hands. I sat for a fifteen minute break: a drink and walnut brownie or a flapjack. I counted every other quarter hour as £1 each, £16 to spend in Tammy Girl afterwards.

At sixteen, I was allowed a longer shift, and a longer break. A whole lunch, whatever I liked. A slice of quiche and rosemary roast potatoes. Now I served the customers, would you like salad or rosemary roast potatoes with that? Sometimes the quiche also had potatoes in it. I graduated to basic sandwich making, to pouring a batch of brownies into large sheet pans. Even when I was the one to remove the tins from the oven, and place them in the cooling racks, I still tried to pick them up minutes later with my bare hands.

Hot things are hot, I reminded myself, as a way of saying, you idiot. My little brother was old enough to clear the tables now. Hot things are hot, I told him, as a way of telling myself. As if I was wise now. I still burned myself a lot. We were in a rush to get through lunch, to sit down one by one, for our own breaks. Or, the rush and bustle of lunchtime in the small café made us feel important. We knew the food was delicious, and looked forward to eating it ourselves.

I stopped working there when I went to university. When I was lucky enough to go to university and not worry about money. Or, I returned for a few shifts over the winter holidays after the first term, until my mother gently suggested I take more time at home, since my dad was in bed, sick. He didn’t come downstairs for Christmas. Our lunch was subdued enough to hear his movements in the bedroom overheard. He died after the New Year. I didn’t go back to work, nor to college for a week. My brother went in for his usual Saturday shift, because that was what made sense to him.

There was rosemary at the funeral. For remembrance. Or, there was rosemary at my grandmother’s funeral years later. She picked her plot next to his on that day, which made sense to her. No gravestones. They are both trees now.

–

This was the beginning of my story which was supposed to be about learning to cook, about mussels. Or, this was the beginning of adulthood. Or, I didn’t know then how precious it was to reach 19 years old and only then have to grow up –

–

I worked in a kitchen again after I arrived in Paris to live. Or, when I arrived here the third time, without a deadline. Once for a month in a chocolate shop, twice for an internship in a museum. The third time after university, to pay rent with my own money.

Or, I paid rent for a year on an English teacher’s salary. Then I wanted to do a pâtisserie course, and I could choose between nine months at a prestigious school for the cost of two English Master’s degrees, or a state school and apprenticeship that would pay me two thirds of the minimum wage. I chose the latter, and asked my mother if she would pay my rent just for a year, €600 a month, and my two thirds would cover the rest of my life. I thought I was very grown up.

I burned myself a lot as part of my apprenticeship. I took pride in it. I remember the triangle scar on my forearm from trays of chocolate sponge, and the moon-sliver from a cauldron of crème pâtissière. Or, I remember writing an essay about those scars, which were light enough then that they have disappeared now, a decade later. There was a hierarchy of morning tasks: the oven was in the middle, mixing creams at the bottom (my job). Icing and decorating the cakes was the most important.

–

I wanted to write about friendship and creativity and time and I would acknowledge money was there in the background, of course, but it seems to be the icing over everything –

–

This weekend I went to see a friend for lunch. A friend, an ex-boyfriend? A friend I thought I was in love with for a year. We never said what it was, until I said that it was over. That I did want to stay friends. I meant it, I didn’t know if it would happen, if he would even stay in Paris. Now it has been so many years that he feels like family.

Or, this weekend I went to see a friend to play pingpong. He said we should walk down to the park at lunchtime, because most of the French would be inside at their tables. It was a glorious sunny Saturday, more October than September. The kind of weather that is a gift if you are open to receive it, the kind of remark that is a slap in the face if you have only the energy in the morning to wake up and put one foot in front of the other.

One of the three tables in the park was open. It had a speckled granite surface and a metal barrier as a net, and the line down the middle was chipped enough to make the ball bounce off at an angle. We had never played any sport with or against each other in all this time. (‘Sport.’) I had asked him if he was competitive, but there is no good answer in the abstract. It can only be shown over time and familiarity. It is intoxicating on first dates to ask those kinds of questions, how do you define yourself. I’m a Noun, I have always been Adjective. My flaws are numerous but here are three curated ones for your appraisal.

–

Pingpong is free to play outside, if you have the racquets and balls and the rent money to even be in the city –

–

We played for an hour. My friend flexed his hand and stretched his forearm between rallies. Two weeks before he had spilled a whole kettle of boiling water over it. There wasn’t an angry scar so much as splotches of white skin within his tan. I asked if it hurt, if the skin was too tight. He said no, that the new skin was more sensitive to the sun than the rest, the sun that was too warm for October. He also said that for a serious burn, you need to hold it under running, tepid water for 15 minutes. 15°C, 15cm from the skin, 15 minutes. (Time that I do not have on a morning bakery shift.) The pharmacist said that covering it in olive oil was not in fact the best choice – did I mention, my friend is Italian? – but it did protect him from the air until he could buy the pharmaceutical cream.

We walked home along the canal de l’Ourcq, past the poissonnier. He bought a kilo of mussels in their shells for the two of us, one tomato and some salad leaves. I had never made mussels before. For me, they were in the category of bistro food: delicious and time consuming and just about affordable to get someone else to do the prep. Also in that category: steak-frites, bearnaise sauce, crème brûlée. What a luxury to live in a city where middle of the road restaurants still exist. Not chains. Not a fast food / fine dining binary. The French love a bistro burger. I do too.

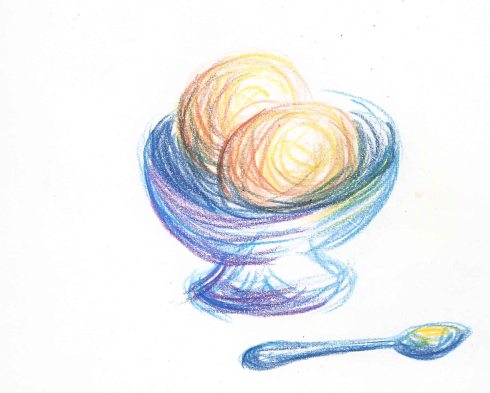

The mussels were already quite clean from the fishmonger, so we rinsed them under cold water and my friend showed me how to chip off any tiny barnacles with a small knife. I pulled at the threads between the halves, their little beards, until they snapped, and threw away any cracked shells. He heated some olive oil in a wide, flat pan with garlic and a bayleaf (fresh would have been better, he said) and some thyme. While I diced the tomato, he poured half a cardboard juicebox of white wine into the pan. The hot oil hissed and spat and a drop landed on the ghost of his burn. In went the mussels and the tomato, until the shells opened on their hinges.

Then we ate several bowlfuls each, dipped bread from my bakery into the sauce. Did you add salt? I asked. No, that is just the taste of the mussels. I drank the rest at the bottom of the bowl. We had coffee, and walnut liqueur from his aunt. I asked him about the time when I came to visit his family in Italy, questions I was too shy to ask then, and he reshaped my memories for me. Then I realised I was High Fidelitying him, worse, that I had reread the book only a week before. I asked him about his dad’s recipes, to bring him back to life as well.

–

I thought this would be about time but not necessarily the numbers of it. I was thinking about the vast abstract nature of time, how it is undefinable but finite. And now I am counting it forwards and backwards, 13 years since, four more years until –

–

I had been feeling for a while, for six months, for most of my adult life, that I didn’t have enough time to go to work, to go to school part-time, to be alone, to be sociable. To maintain all the threads of connection. And to leave space for new discoveries. The most recent solution was to live a pretend village life in the city for my one day off a week, to walk to the market and say hello to the crepe man, who is so friendly to everyone that it doesn’t matter if he recognises me or not. And if I was very lucky, people I knew would join me in my limited circumference, for a coffee in the flea market, for a beer in my favourite bar.

So I made loose plans to bump into some new neighbour friends, a couple, at a local vide-grenier, a secondhand street sale. We wandered and looked at old shoes and DVDs and a suitcase full of postcards. The walk became coffee, or, it’s lunchtime actually, are you hungry? And we sat at a perfectly ordinary local bistro. The table next to us received steaming saucepans full of mussels, but they were the last ones. I had fish and chips instead. I discovered that the couple had met twice over, and that there were enough threads of connection that it was curious we were not all already friends. Two of us had taught English for the same company, we had friends in the UK in common –

–

I wanted to write about time and love and –

Here my pen runs dry. Not a metaphor, it runs out of ink. It was the Muji pen that my favourite cousin loves, that reminds me of her. In the time it takes to find a boring biro, I remember that just recently I have been writing and talking to other cousins, who have become grown up friends, more than family. That now I have more than one favourite. And, some of my friends have crossed over into family without my noticing where the line was drawn.

I wanted to write about time and love and creativity and the beginning point was those mussels, because they were so new and delicious I knew they would be a clear future memory, because this was not the beginning of the friendship, because our conversation over the mussels sparked more conversations with more people –

–

I realised today, cycling under the sun, something that felt as stupid and important as, hot things are hot. There are so many things to say and do and create, and there is never enough time. And sometimes that feels like guilt and pressure and an unacknowledged fear of death. And equally, not enough time to say and do everything is the biggest luxury of them all. If the only barrier is our own mortality, our own finite time between birth and death and working for a house and food, then we are lucky.

Time is money, money is time. Or, is it? Infinite money will not buy infinite time. So they are not equal.

You only need some money. (Only. I tried to leave this bit out but to do so is definitely cheating. I don’t pay rent any more. My family gave me enough money – an inheritance, a gift – for a deposit on a studio flat. Now I pay a mortgage that is sustainable on a baker’s salary. Which is to say, not possible for most bakers.)

If I didn’t have to work, I would have more time in my week, and I still couldn’t read all of the books in the world. I could buy them all. I would still have to choose only a few to read. But I can already read a book, and swap it with someone I love, and talk about it later. Or have them narrate plots for books I will never read, and that still counts as creativity and connection and warmth.

Substitute books for whatever else you like in the metaphor: how lucky if the only thing to get in the way is time. Or death. To love someone so much that you will never be able to tell them everything over a lifetime, yours or theirs. To die with more to say. To wish for just a bit more time. Because if time is finite, if there is never enough, then the love itself is infinite.

So I thought about this on my bike, still in the curious sunshine – too warm, a warning, another deadline – and I felt lucky. Or, I felt silly, like a teenager, realising important things as she burns her fingers on a spliff. Hot things are hot. Time is finite and love is boundless.

Or, I had a nice weekend with nice people, and sunlight is good for the brain. Vitamin D. And I never smoked as a teenager, I wasn’t cool enough –

–

This new skin feeling, too sensitive to the sun, is impossible to notice continuously, because work and money and other people get in the way –

Or, sometimes you want other people to get in the way. Sometimes you need to forget, and get burned, and remind yourself again –

Or, it is a luxury to have a web of connections, to want to hold all the threads. And it is a privilege to have the means to try. Like the bistro meal, it is just about affordable: a phone call, a stamp, a walk, a message to say, I dreamed of you last night –

–

–

–

–

–

This was inspired by:

We Are Watching Eliza Bright by A.E. Owens, a novel written in the first person plural, with the word Or as infinite possibilities, and full stops optional

The film Mothering Sunday, and more importantly, the conversation with Nafkote about it afterwards.

Mussels with Paolo.

Brandon Taylor on tennis and writing.

Anne Helen Petersen on community and showing up.

This is not a newsletter. This is not a new beginning, or a promise to write more. My last two posts were in two different Octobers, which means I may have accidentally shifted onto an annual rhythm. This is a blog with pictures, which overlaps almost exactly with my Paris timeline. But there is an email signup link if you like, somewhere here on the right –